This piece015 Archivespart of an ongoing series exploring what it means to be a woman on the internet.

When the world realized late last year that you could convincingly superimpose one person's face onto another person's face in a video, it was because men used the "deepfake" technology to force their favorite actresses to appear in their pornography of choice. Of course, they boasted about it on Reddit and 4chan, which prompted a frantic debate about the ethics of using artificial intelligence to swap people's faces -- and identities.

SEE ALSO: AI-powered tool helps domestic violence survivors file restraining ordersIn the midst of that controversy, two California lawyers with expertise in digital privacy and domestic violence advocacy found they were equally alarmed by how the technology was poised to destroy the lives of unwitting victims, some of whom they might one day aid or represent in court.

Imagine, for example, a survivor of domestic abuse discovering that her partner used deepfake technology to overlay her likeness onto a porn actress's face, and then deployed that counterfeit image or video as a means to control, threaten, and abuse her.

Adam Dodge, legal director of the domestic violence agency Laura's House in Orange County, California, and Erica Johnstone, partner of a San Francisco law firm and co-founder of nonprofit organization Without My Consent, were horrified by the possibility. Then they decided to do something about their fear.

"A lot of people didn’t even realize this technology existed, much less that it could be misused or weaponized"

In April, they published an advisory for domestic violence advocates, detailing how fake video technology could add another brutal dimension of trauma to emotionally and physically violent relationships.

"A lot of people didn’t even realize this technology existed, much less that it could be misused or weaponized against the population we serve every day," says Dodge.

The reality of deepfake technology will unnerve women who specifically avoided creating intimate photos or videos so they'd never have to worry about seeing themselves in nonconsensual porn, or revenge porn, wherein a victim's intimate photo or video is posted online without their permission.

Open-source scraping tools that pull photos and videos from publicly available social media accounts and sites can be fed into computer software programs capable of churning out pornographic deepfakes in a matter of hours. The perpetrator can effectively hijack someone else's identity, make it look like she appeared in pornography, and leverage search engine optimization and cybermobs to target her.

"This is nonconsensual porn on steroids," says Dodge.

In May, Rana Ayyub, an investigative journalist in India, wrote about being digitally attacked on social media by users who spread a pornographic deepfake video of her.

"The slut-shaming and hatred felt like being punished by a mob for my work as a journalist, an attempt to silence me," Ayyub wrote. "It was aimed at humiliating me, breaking me by trying to define me as a 'promiscuous,' 'immoral' woman."

This Tweet is currently unavailable. It might be loading or has been removed.

Neither Dodge or Johnstone knows of a case where a domestic violence victim's abuser created a pornographic deepfake as revenge or leverage, but both believe that scenario is imminent. They're choosing to publicize the possibility now because they both watched in the past as law enforcement, lawyers, judges, and advocates scrambled to respond to the rise of nonconsensual porn.

The problem, as Dodge and Johnstone describe it, is that some states learned from this experience and should be able to offer victims of fake video technology protection and recourse through the legal system, while other states remain woefully unprepared.

In California, for example, domestic abuse survivors whose former or current partners have posted nonconsensual porn of them can file a restraining order through family court. The same should be true for deepfake victims, says Johnstone, since publishing doctored images or video could count as false impersonation, stalking, harassment, or other forms of intimate partner abuse defined by state law. The perpetrator might also violate the law by stalking or engaging in harassment and intimidation to obtain the hundreds of photos needed to use a face-swapping AI program or app.

This Tweet is currently unavailable. It might be loading or has been removed.

Additionally, the state of California, under the leadership of then-Attorney General Kamala Harris, launched an eCrime Unit in 2011, and eventually provided training for investigators and prosecutors with specific emphasis on "cyber exploitation" and nonconsensual porn.

Johnstone imagines that if a victim who is well-organized, persistent, and has a compelling narrative tries to file a police report against her perpetrator in California, she'll have a good shot of encountering an investigator with experience or training. She also shouldn't be funneled into a legal system that's ambivalent or even hostile toward her cause. (Johnstone created a checklist so that people in other states can advocate for similar protections.)

Yet nonconsensual porn laws vary by state and training can only do so much. It's impossible for law enforcement to investigate every case, and it may not result in a criminal sentence when they do. Victims may need to hire an expensive private attorney, and even then may not win financial restitution in civil court.

Carrie Goldberg, a prominent New York lawyer who's taken on numerous nonconsensual porn cases, says the prospect of how deepfake victims will be treated is worrisome.

"Even if there is [a nonconsensual porn] law in their state, cops can be disbelieving or make my clients feel like they're getting upset over something trivial," Goldberg wrote in an email. "So, imagine if they walked in and said, 'Hey, a doctored image of me participating in a gangbang is ruining my life.' They’d be dismissed at a greater rate."

This Tweet is currently unavailable. It might be loading or has been removed.

Since there is no federal law that protects victims of nonconsensual porn, and state laws don't include commercial pornography in their policies against revenge porn, Goldberg says civil lawyers may need to use "creative tools" like copyright infringement and defamation suits to seek justice for their clients.

Johnstone sees a pro-active role for the clients themselves. While she's wary of issuing blanket statements about restricting access to one's personal videos and photos -- "a certain amount of trust is necessary for relationships" -- the advisory she wrote with Dodge recommends that victims make social media accounts private, ask family and friends to remove or limit access to photos that include the victim, and use Google search to identify public photos and videos for removal.

Women who may not suspect their partners of using fake video technology should still know the warning signs, which include asking for access to and downloading a cache of personal photos as well as frequent requests to pose for images or videos. Johnstone recommends setting "house rules" on a case-by-case basis about when photos are taken and in what circumstances.

"When someone flees an abusive relationship, [the abuser] looks for ways to recapture that level of power and control"

"If you want to be really cynical, assume this person would use whatever content you give them access to [in order] to shame you and humiliate you online," she says.

If that sounds like a far-fetched dystopia, know that Johnstone has represented clients whose profile images, consensual yet private intimate photos, and pictures from average photo shoots were used to embarrass them digitally, in perpetuity.

For victims of domestic violence, Dodge says deepfake technology poses a particularly malicious threat: "When someone flees an abusive relationship, [the abuser] looks for ways to recapture that level of power and control, and threatening to release a video or photo is a very powerful way to do that."

Even if the victim knows that photo or video is fake, she'll endure the painful task of trying to convince others that it's false -- or she may even decide to stay with or return to an abuser, believing nothing she can do will stop his behavior.

The debut of fake video technology, says Johnstone, marks a new phase in our tech-obsessed society, and it's poised to harm the most vulnerable among us, like domestic violence victims, and that fundamentally threatens our understanding of what's real in the world.

"The next generation of identity theft is not that you're reading fake things about a person but you’re also seeing them playing out," she says. "You used to say, 'You can’t believe everything you read.' Now it's that you can't believe everything you see."

Topics Artificial Intelligence Social Good

'The Witcher' Season 3's ball costumes are packed with hidden clues

'The Witcher' Season 3's ball costumes are packed with hidden clues

The 15 best K

The 15 best K

The 15 best K

The 15 best K

The Anatomy of Liberal Melancholy

The Anatomy of Liberal Melancholy

HBO's 'Insecure' is streaming on Netflix

HBO's 'Insecure' is streaming on Netflix

This Overdue Library Book Wins, and Other News by Sadie Stein

This Overdue Library Book Wins, and Other News by Sadie Stein

How to Prepare for the Past by Brian Cullman

How to Prepare for the Past by Brian Cullman

Draper vs. Arnaldi 2025 livestream: Watch Madrid Open for free

Draper vs. Arnaldi 2025 livestream: Watch Madrid Open for free

The Feelies at Maxwell’s by Josh Lieberman

The Feelies at Maxwell’s by Josh Lieberman

'Mario Kart World' Nintendo Direct: 3 takeaways

'Mario Kart World' Nintendo Direct: 3 takeaways

Rebecca Walker, Maui, Hawaii by Matteo Pericoli

Rebecca Walker, Maui, Hawaii by Matteo Pericoli

Apple's new 'Time to Walk' feature officially lands on Fitness+

Apple's new 'Time to Walk' feature officially lands on Fitness+

12 things the internet taught us we've been doing wrong our whole lives

12 things the internet taught us we've been doing wrong our whole lives

Character AI reveals AvatarFX, a new AI video generator

Character AI reveals AvatarFX, a new AI video generator

Beatrix Potter, “Study of a Spider” by Sadie Stein

Beatrix Potter, “Study of a Spider” by Sadie Stein

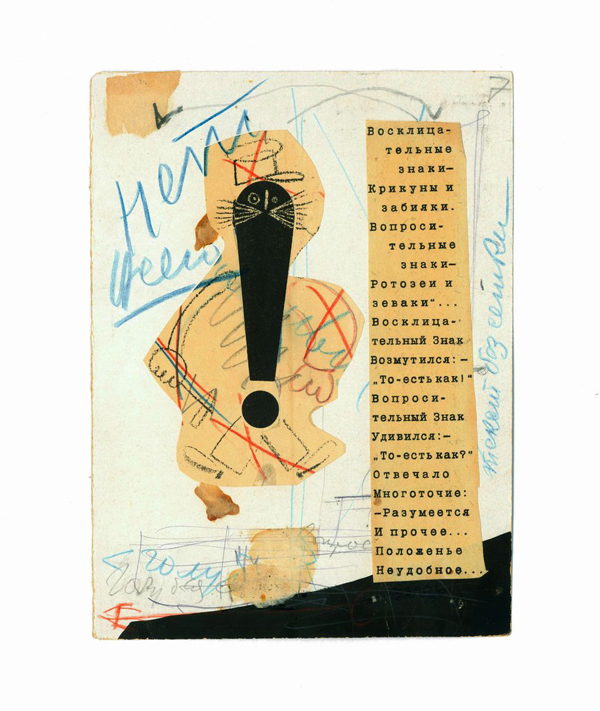

The Golden Age of Soviet Children’s Art by Justin Alvarez

The Golden Age of Soviet Children’s Art by Justin Alvarez

Man Steals Books to Find Meaning of Life, and Other News by Sadie Stein

Man Steals Books to Find Meaning of Life, and Other News by Sadie Stein

Happy Birthday, Raymond Chandler by Sadie Stein

Happy Birthday, Raymond Chandler by Sadie Stein

Kid's impassioned message to bullies finds support all over the internetKid's impassioned message to bullies finds support all over the internetDustin Hoffman accused of groping coWhat to expect from Mobile World Congress: Samsung, Huawei, and more25 books and stationery items to gift your nerdy bookworm friendsPentagon will allow transgender people to enlist in military despite Trump's tweetsChristmas time means loads of sneaky cats getting stuck in treesThe Pope has way too much faith in the way we use social mediaCards Against Humanity tries to disrupt wealth inequality with latest campaignPicture in picture is finally coming to YouTube for iOS usersEllen DeGeneres, Uma Thurman speak out against Roy MooreDramatic video shows workers frantically freeing horses amid wildfireDisney orders Gaston from 'Beauty and the Beast' miniseriesEverything to know about that other Loki in 'Loki''Rick and Morty' Season 5 premiere review: "Mort Dinner Rick Andre"Alabamian Channing Tatum asks his home state to do the right thing, for the love of GodDisney orders Gaston from 'Beauty and the Beast' miniseriesSexual abuse in the music industry gets spotlight with #MeNoMorePixar's 'Luca' is the ultimate summer vacation fantasy: Movie reviewRoy Moore lost the election and everyone made the same joke 11 of the most hilariously awkward live British TV moments of 2017 John Mayer (and the internet) accepts the #KyloRenChallenge Coldest New Year's Eve in 70 years awaits revelers in Eastern U.S. Lake Erie's 5 feet of snow sure makes for some weird ass stunts Mark Hamill 'regrets' sharing his doubts about 'The Last Jedi' Billie Lourd remembers Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds with touching Instagram posts Mom, who is sadly not our mom, crochets 'Golden Girls' cast for son's Christmas Apple Store in Chicago has a big winter design flaw Vin Diesel named top Poor, unfortunate soul gets his penis stuck in a London subway gate Lego cars are helping university physics students stay in school Tech companies need to stop making gadgets look like trash cans Will Ferrell's Rose Parade coverage was flooded with one 14 times Mark Hamill's Twitter game was quite simply out of this world Don't worry, the world could still end before 2017 is over! 'Game of Thrones' star Instagrams precious baby pic and fans are gushing Meghan Markle is the princess of British Google search trends in 2017 Dustin Hoffman's accusers thank John Oliver for confronting him Parents turned their daughter's request for Lorde tickets into an amazing prank Apple issues apology for slowing old iPhones down

2.4898s , 8248.6640625 kb

Copyright © 2025 Powered by 【2015 Archives】,Feast Information Network